You may recognize by now my tendency to give meandering introductions. This post offers a discussion of using dialect in a fantasy novel and ends with an example from my WIP, but I can’t seems to get there without narrating my own cultural history. If you want the ideas without the personal history, skim down and begin reading at the section titled, “Why Use a Dialect.”

Unprepared For a Multicultural World

I grew up in a White, monolingual, middle-class, suburban household with two college-educated parents. My father’s family seems to have been English-speaking all the way back, as my paternal grandmother’s side (named Sharpless) can be traced to the Quaker settlers of Pennsylvania in the 1600s. My father’s father grew up dirt poor, attended the University of Arizona, and won a Rhodes Scholarship which he had to refuse because it wasn’t enough money for a young man without resources. My father’s mother was the daughter of missionaries in Hawaii before it became a state. She and her sister both became artists, and my great-aunt Ada Mae Sharpless studied art in Paris and is a listed sculptor. They weren’t wealthy, but they had disposable income.

My mother’s family (named Berlin), German immigrants of the 1880s,were peasants who may have been displaced by mechanization, as commonly happened in Europe during that period. As teenagers, both my great-grandmother and great-grandfather immigrated to the U.S. simultaneously, on the same ship, in two complete family groups from Wolfshagen, Germany–about a dozen people in all, including many siblings and (as it later developed) all four of my great-great grandparents. Then, both families settled in the Chicago area where there was a large German immigrant population. Although the two families had previously known each other in Wolfshagen, relatives I’ve talked to insist it was a coincidence that they immigrated on the same ship and then settled in the same place. The romantic in me wants to tell a different story, but my great-grandparents didn’t become sweethearts until several years later.. They and their children–including my mother’s father, George—were bilingual and bicultural until the Great War, when German-Americans found it advisable to erase their cultural heritage. George grew up bilingual but almost never spoke German, and his three daughters only spoke English.

My grandparents on both sides were professionals—my mother’s parents owned a flower wholesale business, and my father’s father had an administrative job with the city—but they lived on or owned farmland in California. My parents, Don and Gretchen Marks, met in a 4-H program when they were in high school. They both earned degrees from the same college, intending to be high school teachers. By the time I was born, the second of four children, my father had a white-collar engineering job and my mother was a suburban housewife. I grew up in a 1950s housing tract, and attended a tiny private elementary school with a dusty playground where I often went off to sit by myself near a honeysuckle bush. (I was a weird kid.) I first saw a Black person in fifth grade when I started attending public schools. It wasn’t until I was in graduate school on the east coast that I experienced a rather unsettling perspective shift, and realized how culturally- and linguistically-impoverished my 1960s upbringing had been, despite my parents’ valiant efforts to raise well-educated children.

I don’t have any inherited cultural knowledge that I can dig into for writing material. But using another culture’s dialect as window-dressing for a novel seems potentially offensive. Even if I manage to do it in a respectful, non-caricaturing manner, it still seems like cultural appropriation. Most of book I’m writing now is in my native language (“standard” English), but I want a particular group to have a different dialect, and therefore my only option is to invent one, while hoping that I won’t inadvertently create a dialect that is already in use somewhere.

Why Use a Dialect?

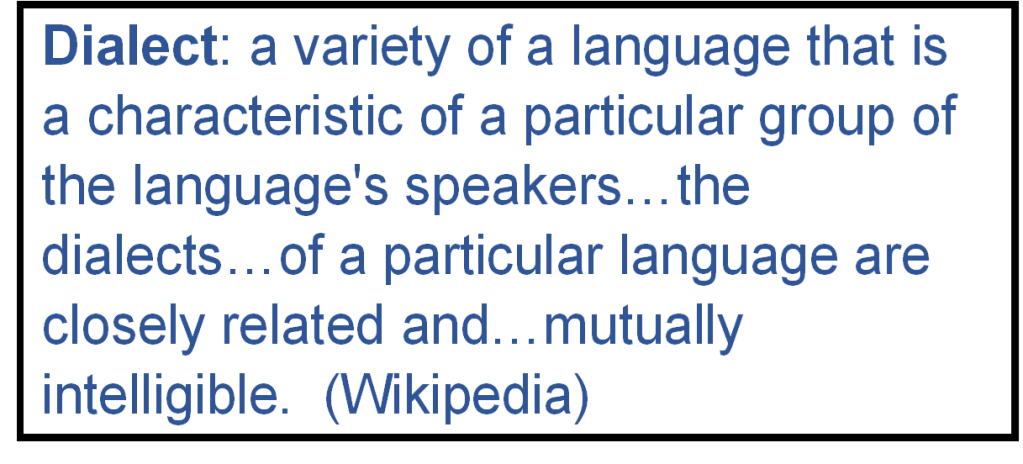

Fantasy writers must invent worlds that are alien to, yet intelligible to, their readers. We can make the language strange by various means—such as by using archaic words and sentences. But if we make the language too weird, it will be too difficult to read. We could make the language unapologetically current, but unless it’s a contemporary fantasy it will seem anachronistic or comedic. (Even then, it could be comedic. “A dragon walks up to me and asks if it can bum a smoke” seems like the first line of a joke.)

My novel in progress is written in the voice of a protagonist who comes from an oppressed class that has its own dialect, but she is able to “code-switch” or move between dialects. Conversations between Rubbishers will be in their dialect. However, her account is intended to be read by members of the upper class, and therefore her narrative is primarily in my native dialect, “standard” English, with occasional incursions by the Rubbisher dialect.

I want to use a dialect to emphasize the class differences that are an essential part of this story. After not a great deal of thought and research, feeling fortunate that I have studied linguistics, I’ve decided the features of the made up dialect will be influenced by thematic aspects of the story, without worrying about how likely it is that such a dialect would develop in the real world. (I think it could happen with a creole, but I am no expert. The dialect I came up with does feel like a creole.) The primary feature of the dialect is that it has only a present-tense. This grammatical focus on the present thematically parallels that fact that Its speakers are forced to survive from moment to moment, with little understanding of how events in the remote past have led to their current conditions, and no reason to expect that anything they do in the present will have a significant impact on the future.

The Rubbisher Dialect

Here are the characteristics of the draft dialect, most of which are features of existing languages that I’m shoehorning into English. I’ve rewritten a conversation (below) according to these rules, and so far the dialect seems workable, though I won’t know how much it will irritate my readers (that’s you) until I get some feedback.

- Present tense only.

- The phrases “before yesterday” and “after tomorrow” signal the past or the future.

- Participles (-ing) indicate an ongoing/chronic state, but aren’t paired with an auxiliary verb, such as a version of “be.” (Example: “I thinking,” not “I was thinking”)

- When the grammatical subject is known to all speakers, it is unstated. (If everyone is talking about a particular person’s eating habits, they would say “Eats lots of corn,” not “Bill eats lots of corn.”)

- No compound verbs (verbs composed of many words, such as “would have been eating.”)

- As a general rule, utterances are minimalist, similar to a telegraph message.

A Passage from the Book (Feedback Requested)

“You hear about Pepper?” Ananis said.

“Which Pepper?”

“Rag-sorter. Coming to the stall for tea every afternoon, because he breathing dust all day. Short, no hair on right side, blind in right eye.”

“I don’t know him.” But Ananis was the type of person who knows and remembers everyone in Rubbishtown, so I added drowsily, “What about him?”

“Before yesterday, the Legionaries come for him and five other rag-sorters, and kill them right there in the sorting yard. Because one of them finds something in the rags and keeps it, and the rest know what they did.”

“So Legionaries say.”

“Yah, well. We never knowing what’s truth and what’s lesson.”

I said, “We not needing more lessons. Even a very stupid person not keeping forbidden things.”

“Yah, well. I wondering why a person keeps a thing like that. Gets all their friends killed.”

We lay side-by-side, warm on our backsides and chilly on our fronts, but not cold enough yet to put our clothes back on. There was a swirl of stars, like they were going down a drain so slowly that your impatient eyes couldn’t see the movement at all. I said, as though I had been thinking about her question, but not as though I knew the answer, “Maybe they wanting something, and they find in the rags a thing that maybe gets their desire.”

“Wanting it more than they want life?”

“I guess they pretending to themselves that they being careful, so no worry.”

“Big pretending.”

“Some people lying to self.”

“Surprising, they being so stupid,” said Ananis. “Usually stupid ones die without growing up.”

Please use the comments box, below, to tell me what it’s like to read this dialect, and to offer any advice. Thanks!

-

I love this. My only suggestion would be to drop the articles, a and the. It seems as if a simple language might not have them.

LikeLike

-

Thank you for that suggestion. I’ll try it and see what happens.

LikeLike

-

-

I missed reading this when you first posted it! I’m not sure I agree about dropping articles — much would depend on how the dialect evolved. If the speakers originally spoke a different language entirely, the articles could easily be lost. But if it devolved directly from the original, more complex language? The pronunciation of the articles might alter to some minimal form, like “th’ ” for “the” and the “a” getting stuck onto the previous word.

LikeLike

-

(and I don’t know why WordPress added “likelike” to the end of my comment!)

LikeLike

Leave a reply to Laurie Marks Cancel reply