Before Google, we had card catalogues and reference books. But to hunt down the source of a few words lingering in the mental space was really quite impossible. I suppose we’d just ask a librarian, “Where is the phrase ‘fleet time’ from?”—assuming, of course, that one wasn’t too shy to ask–and she (usually it was she) would track it down somehow. But I simply typed “fleet time” into Google and the Internet informed me that it’s the title of a Chinese film (“Fleet of Time”), that the current time in Fleet, England is 1:30 PM, and the acronym FLEET stands for Fast Local Emergency Evacuation Times. I added the word “poem” to my search, because usually these phrases are fragments of poem that got themselves glued to a randomly firing neuron, and I received some links to poems comparing humankind to fleets of ships. And I also got this:

Sonnet 19: Devouring Time, blunt thou the lion’s paws

BY WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE

Devouring Time, blunt thou the lion’s paws,

And make the earth devour her own sweet brood;

Pluck the keen teeth from the fierce tiger’s jaws,

And burn the long-liv’d Phoenix in her blood;

Make glad and sorry seasons as thou fleets,

And do whate’er thou wilt, swift-footed Time,

To the wide world and all her fading sweets;

But I forbid thee one more heinous crime:

O, carve not with thy hours my love’s fair brow,

Nor draw no lines there with thine antique pen!

Him in thy course untainted do allow

For beauty’s pattern to succeeding men.

Yet do thy worst, old Time! Despite thy wrong

My love shall in my verse ever live young.

I just love that insane double-negative, “Nor draw no lines there.” In this sonnet the words “fleet time” don’t appear as a phrase, but the verb “fleets” is here (at the end of line 5, to rhyme with “sweets”) and “Time” sits at the end of line 6: “swift-footed Time” –with Time capitalized to indicate that the poet is addressing a personification of time. So maybe that neuron was remembering those two words as visually adjacent, above and below each other in the sonnet.

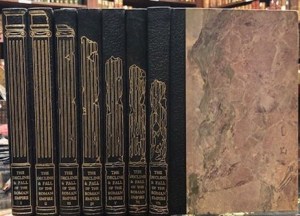

And in case you’re wondering–for which I don’t blame you at all–I acquired complex sentence construction from multiple re-readings of Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte when I was at an impressionable age. My mother had taken a college course on children’s literature, and there learned that she should fill her bookshelves with great literature, a task that she immediately launched by subscribing to the Heritage Book Club, which published some truly gorgeous books. I think I was her only kid to take the bait, but I read every book on the shelves except The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. (The artwork on the spines of the boxed set depicted a sequence of a pillar crumbling.)

Frankly, I also may have read every book in the children’s library of Riverside, California. Kids were allowed to check out seven books a week, and my friend Sara Gilbertson and I would each check out the limit, read all our own books, then exchange them and read each other’s books.

To get back to my point, Bronte’s sentences are long and complex, with many nested phrases, like this one, and and an exuberant overuse of colons: sometimes for no good reason. If you get lost in my sentences, blame Charlotte. The paragraphing, however, is all my fault.

As I write this, I’m waiting for my author friend Rosemary Kirstein to arrive. (Do read her Steerswoman series—they are excellent and, incidentally, reasonably priced.) It’s a beautiful cool day, and we’re going to bring a picnic to the local Audubon park and then go for a hike in the woods. We almost certainly will discuss FLEET Time. Because I (happily) am writing five hours and more every day, there’s been a domino effect and I haven’t got time for anything else. The house is filthy, the weeds are encroaching on the flower beds, the food is moldering in the refrigerator. Things I looked forward to and enjoyed, like playing ukulele and painting, have lost their appeal. When I’m not writing, I’m thinking about writing. (My character, Painter, her back to the wall, has done something marvelous—created a series of rooms in a place that doesn’t exist, which can’t be entered or exited. A perfectly safe place. Then she realized she must have water, so she painted in a spigot.) I have all the time I need to write, and no time for anything else. Meanwhile, Rosemary is feeling the passage of time in a different way, which seems to be a hazard of aging: we become aware that time is running out and we wonder how the heck that happened.

It was Rosemary who once said, “You know time really is money, because you never have both of them simultaneously.”

Yet both of us, by surviving long enough to retire, now have both time and money. Not a lot of money and time continues to be fleeting, and we’re forced to take care of and be patient with our aging bodies and brains. But we have both time and money, by God, and we’re using them: for a long conversation, roast beef sandwiches, and a walk in the woods on a beautiful day.

Leave a comment