I know a little about a lot, but I don’t know a lot about a little. I’m a generalist. I research when I need to—but as little as possible because I’d rather be writing. Fantasy writers whose setting is an actual time and place might do a lot of research, as I have done for my incomplete, temporarily abandoned project CUNNINGMEN, which is set at the beginning of the industrial age in a place I’ve never visited. Of course I intend to travel there, but fate keeps preventing me from doing so.

I did spend a day in a historic milltown in northern Massachusetts. I climbed the steep factory stairs, stood in the terrific racket of the antique machinery, and watched a piece of fabric being woven by an ancient industrial loom. When I finally write that book I won’t need to conduct additional research to understand the health effect upon the millworkers, or to understand what they’d feel like after twelve hours in that place.

The best research is experiential.

The Tale of the Quill-and-Fur Paintbrush

In the book I’m currently writing–remember, it’s an apocalyptic fantasy–the primary character is reinventing the lost art of watercolor painting and must make her own paints, paintbrushes, and paper. However, I don’t have to imagine what it’s like to become a painter during an apocalypse, because I became a watercolor painter during the pandemic. However, FedEx delivers my art supplies to my door. Is it feasible for my character, the painter, to make her own brushes and pigments? How would she get the raw materials when she can’t go anywhere? Learning the answers to those questions has been pretty interesting, but the research didn’t become particularly fun until I happened to find some 100-year-old goose-quill and squirrel-fur paintbrushes for sale on Etsy. (Someone somehow acquired a whole crate of them, and I’m guessing the paintbrushes had gotten themselves lost in a warehouse for a hundred years.) I could easily convince myself that I needed an antique paintbrush, because even though I had managed to find instructions (from the 1500s) for making similar quill-and-fur brushes, those instructions assumed that the reader had seen brushes like them before, and was merely reminding them how to go about it. So of course I bought an antique brush. I had to do it.

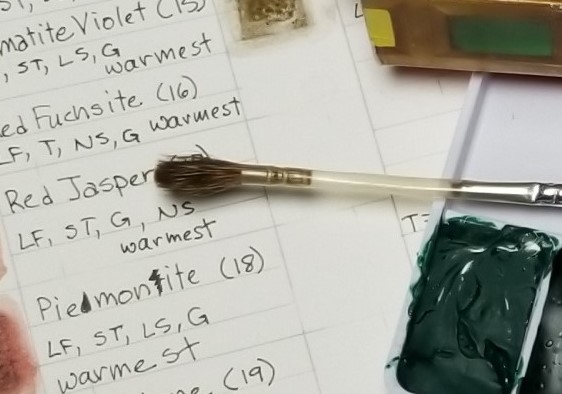

To make this kind of brush, the squirrel fur (from the squirrel’s tail, I assume) is wrapped into a tight bundle using thread. The quill is cut to about two inches in length, and the pointed tip of the quill is clipped off, which turns it into a hollow tube. Then the bundle of fur is pushed down the interior of the quill starting from the wide end until it emerges in the narrow end and is pulled through until about half of it pokes out the end of the quill. The thread wrapping the bundle of fur is then removed, and the fur fluffs out. In my antique brush, the quill has been crimped, which probably helps to keep the fur from falling out. It might have been crimped by soaking the quill, which becomes malleable in water, and then squishing it with a tool of some sort, but I really don’t know. To use the brush, you insert a handle or stick into the quill, and the quill operates like a modern metal ferrule. In my antique brush, the quill was very brittle, but when I soaked it in water it became pliable, and I was able to insert an old paintbrush handle without splitting the quill. It shrank when it dried, and holds onto the handle pretty tightly.

I have used it to paint, and it’s marvelous.

The Tale of the Pigments

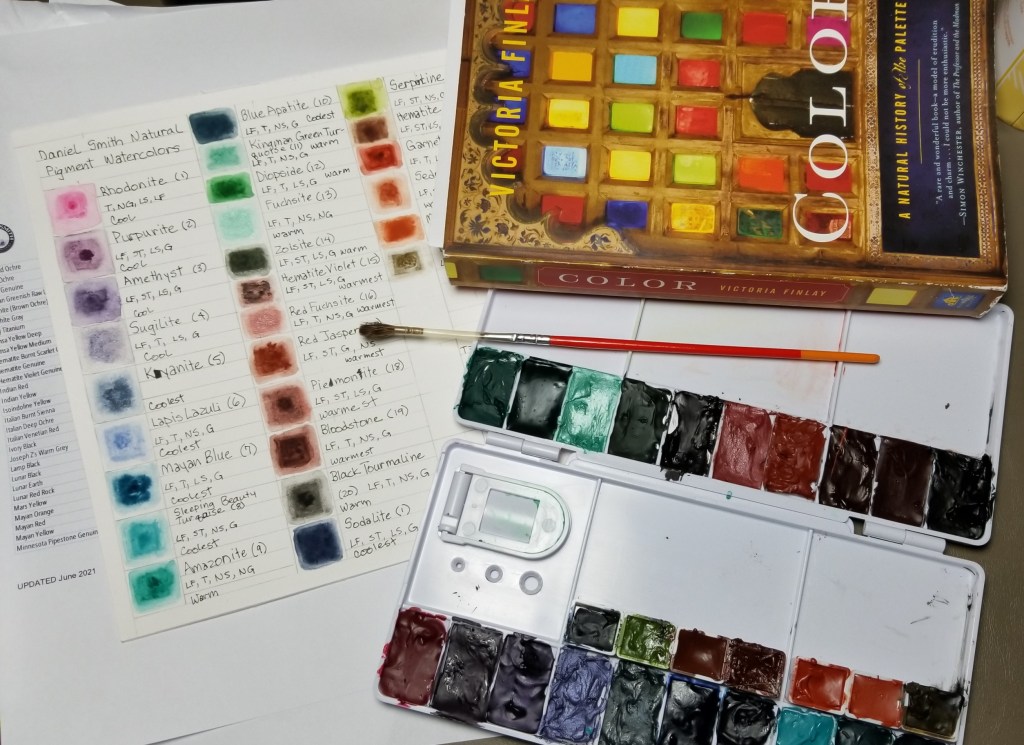

For research into pigments I’ve been reading COLOR by Victoria Finlay, who recounts her world travels searching for the historical sources of original pigments. While I was reading that book, my very sneaky wife was conducting her own secret research. She found that the Daniel Smith company sells an line of watercolor paints made with mineral pigments, some of them insanely expensive. Deb then tracked down an entrepreneur who was composing to-order palettes of Daniel Smith paints, and Deb ordered 20 natural-pigment colors for my birthday. Then the seller threw in seven more colors.

Yellow is a primary color, yet I haven’t found any mineral watercolors that are yellow—the nearest is yellow ochre, which is a brownish gold. So when I paint with these mineral watercolors, I’ll have to manage without yellow, or else use the yellow from my other paintbox. (My painter character can make yellow paint using turmeric, if she can get her hands on some). So far, I’ve only used these mineral paints to make a color chart. Next I need to investigate how the colors behave when mixed with each other. Then I think I’ll pretend to be the painter character and paint one of her paintings, using the natural pigments and the quill brush. I’ll post it here when it’s finished, so watch this space!

Research, Character, Plot

In order to properly create the painter character, I needed to know how she could possibly pursue her passion. My research helped me to see it wouldn’t be possible within the restrictions of her reality, so I adjusted her reality, invented another character who had a reason to help her and the ability to do so, invoked a little bit of deus ex machina so they would happen to find a pigment grinder, decided it was more believable to only give them a few colors rather than a huge palette, and decided they’d make tempura paint instead of watercolor. (Tempura, probably the oldest kind of paint, uses egg yolks as a binder. People can always find a way to keep chickens, which eat anything.)

So the painter can’t get the range of colors she’s yearning for. Until…

And then I had a plot, not merely a series of problems that the painter had to solve, but an event on which the story turns, and now the painter has to figure out what to do about it. Research didn’t give me the story, but information created restrictions that forced me to reimagine how to make the story work.

Fantasy and Reality

And that’s the role of reality in (this) fantasy. Of course the fun of writing fantasy is that you’re not impeded by reality, but that also is a problem. Between the reader and the novel there must be some common ground, or it will be unreadable. And the last thing (this) novelist wants is to invent a world one molecule at a time. Instead, I decide how much of the invented world will be familiar, and how it will be alien. So in the world I’m inventing, they do have the marvelous pink color of rhodolite. And for yellow they have turmeric.

Leave a reply to deb Cancel reply