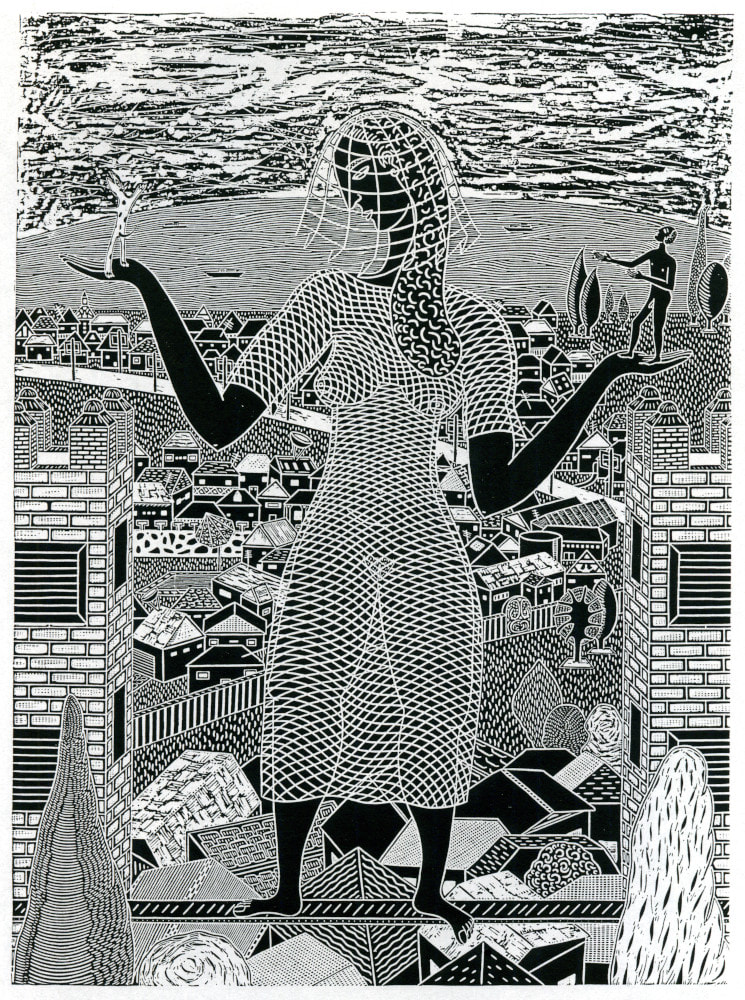

Artist Vera Zulumovski has a linocut print titled “Veiled Woman on a Balance Beam,” which depicts a woman in a sheer dress, standing on a plank above a cityscape, with small figures perched on each of her outspread hands who might be arguing with each other. When I look at this print, I feel the peace and focus that comes from knowing an inarticulate truth. Also, the print inspires in me a complex desire. I want it as the book cover for my work-in-progress. And I long to hang it on the wall beside my fireplace so I can gaze at it while I do the part of writing that looks like I’m doing nothing at all. Or, when I become befuddled and flustered, by looking at it I could remind myself what my book is about.

Scattered Text, Scattered Attention

I’m happy to report that version 2 has achieved 70,000 words. For the last few weeks, I’ve been working on a seemingly simple writing task. My first draft had produced a very short chapter, followed by a normal-length chapter, then a rather long chapter. While revising them, I wanted to combine, then divide, those three chapters, to yield two chapters of reasonable length. Therefore, contrary to my usual practice, I didn’t retype each finished chapter, because I didn’t know where, exactly, one chapter ended and the next began.

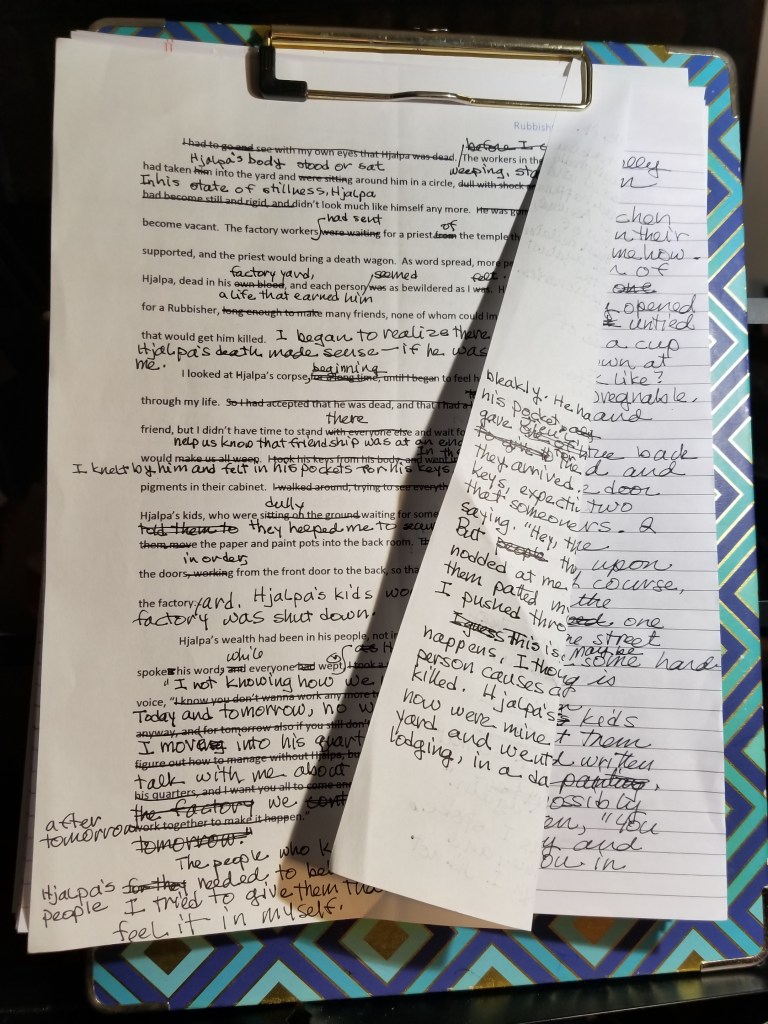

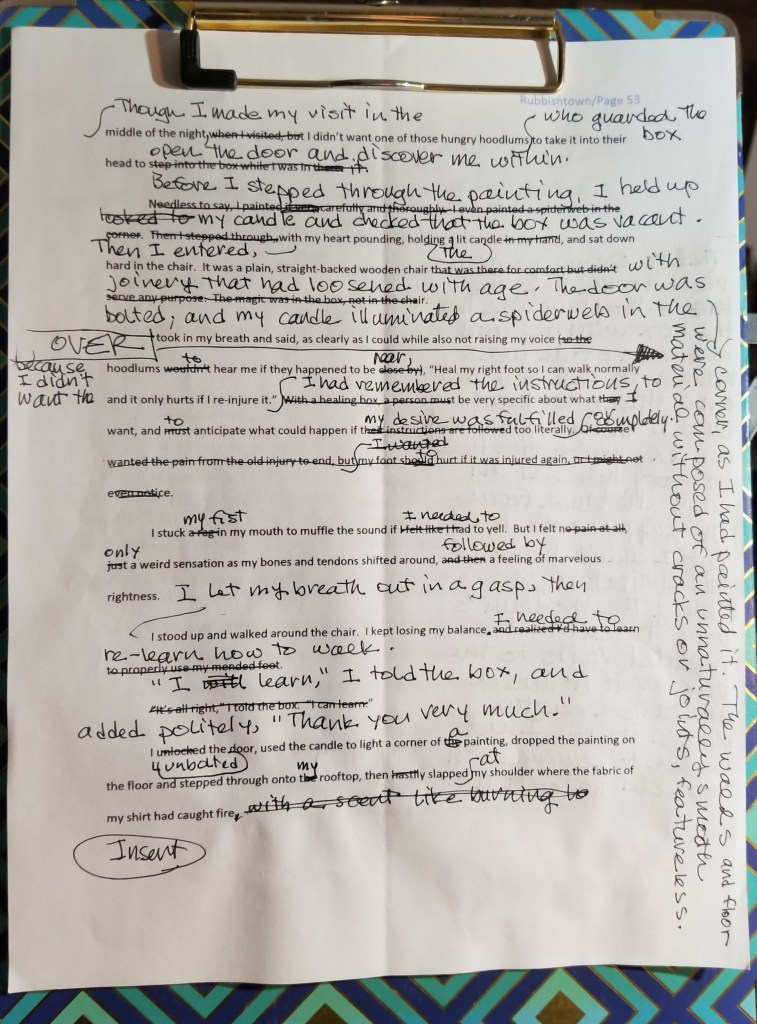

I hadn’t realized how important retyping was. I soon began to feel like I was following a fraying thread through a maze of words. A maze like this:

I am able to read these pages, mainly because I wrote them—but doing so requires a lot of active brainwork, which scatters my comprehension. As a result, I am distanced from and confused by words I wrote just a few days ago. Does this page work? Does it not work? Do I need a different approach? Am I effectively depicting events and my characters’ states of mind? Am I permanently out to lunch?

Who the hell knows?

Magic Wands Need Not Apply

When I type up a chapter, comprehension becomes possible. The light-scatter coalesces into a focused beam, and I can see my book’s multitude of flaws and failures. And that’s okay: Imperfections are rocks that form a path across a river. I step on them, thank them, and leave them behind.

However, retyping isn’t merely a clerical process. I revise as I type, for, as the text progresses from brain to fingers to screen, my attention thumps over speed bumps I can’t resist smoothing over. I fiddle with wording, I refer to the thesaurus, I lengthen, shorten, complexify, simplify, and restructure sentences. My internal ear wants rhythm, harmony, subtle rhymes and repeating sounds. I love this aspect of writing, but I had better not love the actual words; for anything I write today could wind up in the trash heap tomorrow. These are my words; they are not bad words but they must be expendable.

Besides my messy text, other things scatter my attention as well, and sometimes I must police those boundaries that have been encroached upon by phone calls, social media alerts, power outages, tornado warnings. (Yes, we get them in Massachusetts. I bring my papers into the basement, along with a weather radio and my confused but willing dog). Some sounds distract me, but I seem to be fairly immune to visual clutter, a fact that both causes my rather/very/extremely messy house and allows me to be oblivious to it. Other distractions don’t seem to distract me, but they do affect me. I can write in a parking lot, in a doctor’s office, or on a park bench, but I write better and faster in a small, quiet room with decent illumination and a good cup of coffee. I write even better in the woods.

What works for me won’t work for anyone else. In fact, knowing what works is every writer’s continual problem. Once a person knows their particular (but mutable) solution, they must habitually and diligently enact it. No magic wands; even if they existed they’d be irrelevant.

Blankly Staring

One often-overlooked aspect of attention-scatter is not enough downtime. Spacing out is not evidence of scattered attention; in fact it is preventive. For a deep review of this topic I recommend this article by Ferris Jabr in Scientific American. It gives specific, scientific explanations of the not-thinking experience.

Jabr writes, “Downtime replenishes the brain’s stores of attention and motivation, encourages productivity and creativity, and is essential to both achieve our highest levels of performance and simply form stable memories in everyday life. A wandering mind unsticks us in time so that we can learn from the past and plan for the future. Moments of respite may even be necessary to keep one’s moral compass in working order and maintain a sense of self.”

I value and protect the times I’m not doing anything at all. When I was frantically working full time, with another twenty hours a week of commuting, my downtimes occurred during the transitions from one thing to the next: taking a shower, riding the shuttle bus, standing on the train platform, waiting for an elevator, falling asleep. Now, downtimes punctuate each writing day. During those times, I’m not thinking, reading, feeling, seeing—I’m not doing anything. Nor am I trying to do (or not do) anything. If I’m meditating, it’s entirely accidental. But not-doing is essential, not only to writers but to every fraught, overscheduled, distracted, screen-scrolling human. Also to those like me, who sleep too late, read too much, write a lot, then wonder where the time has gone.

My wish for the new year: that all of us would frequently, regularly, shamelessly, do nothing at all.

Side note: Among other things, the job of this blog is to encourage new readers to embrace my books. Therefore, here is a link to Lee Mandelo’s in-depth reviews of my Elemental Logic books, reviews that are worth reading even if you’re not looking to put another book on your to-read pile. (This is not my problem: Every time I add a book to my stack, I feel better prepared for the next catastrophe, just like having a full pantry and lots of batteries for the weather radio.)

Leave a comment