I’ve been doing a lot of patchwork revision: retain text, move text from one place to another, add text to stitch the pieces together in a new way. At the same time, I’ve been expanding on the first draft material I’ve decided to keep, by adding description and dialogue and making the persona consistent. I used to do this kind of work by cutting my typed draft into pieces with scissors and taping the pieces back together, then retyping it on the portable typewriter my insightful parents gave me when I started college. And I still do it on paper, by handwriting the changes and additions, and writing myself notes (“move text from page 22 here,” “insert new text here”). Now, having finished revising and retyping the second chapter, which is only three pages longer though much altered, I’m glad I took a typing class in 9th grade. I thought I needed to type in order to be a writer (I was correct) but that skill also turned out to be necessary to buy my groceries during two unsettled decades that I was writing full time and earning little-to-nothing even with five books in print.

I do a lot of writing by sliding downhill on the seat of my pants. Other writers plan rather than slide, and it works for them. I suspect these planners aren’t any more analytical than I am, but they likely have better memories. I have to lean heavily on the crutch of paper to expand and stabilize a sadly unreliable memory. I write first and plan second because I can’t do it the other way around.

Speaking of patchwork, there’s a lot of patching together involved in this post, and although I’m trying hard to connect it all, you might find yourself losing the signal. Sorry about that.

How Chapter 4 became Chapter 2

When I was composing the first draft, chapters 2 and 3 were a grinding, soul-crushing labor. I felt like I was outside my own story, pounding on the walls (very sturdy walls) to get inside. On my bimonthly visit with Rosemary Kirstein, I discussed a different story problem with her—I don’t even remember what it was—and while I was driving home, it suddenly occurred to me that I could change the plot by bringing in the Judge character, who, having read the first chapter, visits Pinter to give her new instructions. Don’t just explain how to survive in Rubbishtown; Judge says, explain about [agency]. (I am not identifying the agency because it may be a spoiler, and instead I’m using an abstract term from philosopher Kenneth Burke, which designates the instrument with which things are done—the how. (See the sidebar.)

I wrote this scene between Painter and the Judge when I started drafting chapter 4, and immediately realized that the plot driver for this book is everyone’s effort to understand, control, and use the agency. Thus, oddly like magic, I generated the energy I had been struggling to achieve. Apparently, I had been trying to write the wrong book. Now, in revision, it only made sense to cut those two laborious chapters entirely. So Chapter 4 is now Chapter 2, and those two aggravating chapters are in limbo.

Sidebar: Kenneth Burke Sick of living in poverty without health insurance, I enrolled in graduate school in 1996 so I could become a college-level composition instructor. As a graduate student I read some of Kenneth Burke’s writings on Dramatism. Burke argues that human life, like the stories we tell, has five components. (The following is copied from Wikipedia with my additions in bold.)

- Act: “What”, what has been done. According to Burke, “the act” of the Pentad “names what took place, in thought or deed.” (In fiction, this is the plot.)

- Scene: “When” and “Where”. According to Burke, “the scene” is defined as “the background of an act, the situation in which it occurred.” (In fiction, the scene might reflect or reveal interior truths. Also, the scene can cause things to happen thus stealing agency from the agent. This kind of thing happens in the real world, too, as in political, geological, pandemical, and other catastrophes.)

- Agent: “by Whom”, who did it. Burke defines the “agent” as “what person or kind of person performed the act.” (In a work of fiction, the most important agent is the protagonist, the character at the center of the story. Actual people might believe we are agents in our own plot, though any adult certainly knows—possibly to our despair–that our ability to affect the plot of our lives is limited.)

- Agency: “How”, which is associated with methods and technologies. Burke defines the “agency” as “what instrument or instruments he used.” (In a fantasy novel, the agency is likely to involve magic.)

- Purpose: “Why”, why it happened. This is associated with the motive behind the behavior, which is the main focus of the analysis. (An actual person–or a character–might think they have one purpose and turn out to have another. Complex and contradictory motivations help develop complex and contradictory characters.)

Yes, my characters do tell me what to do

Characters have wills. In the case of this book, which the protagonist is writing in prison by candlelight, she has a specific audience, the antagonist. But her words are also being read by the Judge. I suppose that, as is certainly the case with the diligently-writing narrator, the Judge is an aspect of me—the me who reads my own writing and frequently, rudely, not-very-helpfully, exclaims, “What the f—k are you trying to do here?” So these characters represent me, and this work of fiction appears to be about the process of writing. I didn’t set out to be so self-referential, but a lot of my writing is unintentional. Sometimes, my characters dig in their heels and won’t act or think as I want them to, and I have no option except to figure out a different approach for them. Sometimes I get characters together to converse with each other regarding events, so they can help me to figure out what should happen next. This behind-the-scenes contention and discussion disappears by the final draft—thank you, delete button–so that you, dear reader, never suspect how confused I have been by my own project, and so that struggling writers get the false impression that other writers always know exactly what they’re doing. Or that writers are doing all this work by themselves, when in fact they are aided by a bunch of imaginary friends.

Next: I figure out what the new Chapter 2 is about

In a work of fiction a chapter isn’t about anything. Instead, it move from problem to solution to new problem/plot complication, in order to sustain the narrative tension (and, therefore, the reader’s interest). I revised chapter 2 so it begins with Painter pounding on the door of her prison cell (the inciting incident) because she has run out of paper and is nearly out of light. Judge is summoned, and they engage in a negotiation, (progressive complication) during which the Judge demands that Painter explain and produce the [agency], in exchange for which he will allow her to go free (the crisis). Painter agrees (the climax), and then, having been given a fresh supply of paper and candles, recounts the occasion on which she confirmed the existence of [agency]. This narrative is a second discreet story within the chapter, this one set in the past, but it serves as the resolution of the first story, and includes the complication of a near-catastrophe, which Painter uses to explain why, against common sense, she decided to keep [agency]. She acknowledges that her decision-making was not very rational. (This resolution points towards the problems she will encounter in the next chapter.)

Analysis requires theory

To generate this analysis I used concepts from the Story Grid website. Each of their “commandments” (sidebar) has its own page, and you can find the links to those pages at this link. Although the purpose of the website is to sell their book and their editing service, they deliver a lot of ideas at no charge.

I sometimes find this sort of guidance useful, though not usually in the way the guidance-provider intends. Writing overloads the brain (at least it does my pea-brain), and if I overload it further by trying to follow someone’s well-meaning advice and instructions, it leads to paralysis. So I write badly and fix it later.

Now that I do have a chapter to fix, it makes sense to engage in some sort of analysis to figure out how the chapter works and what it needs, and these concepts offer as good an analytical tool as any. A person like me, engrossed in fiction, can easily comprehend how every chapter is a story that links to subsequent chapters/stories. In other words, each chapter has its own story arc, while also participating in the large story arc of the book as a whole. Therefore, fiction writing isn’t easy.

Sidebar: The Story Grid people declare in irritating capital letters that “every UNIT OF STORY” (such as a chapter) is composed of:

- INCITING INCIDENT (“a ball of chaos that spins into the story and knocks the protagonist’s life out of balance,”)

- TURNING POINT PROGRESSIVE COMPLICATION (“The protagonist begins taking a habitual series of steps to restore the balance [and] each of these steps fails…which forces the protagonist to move to their next tactic.”),

- CRISIS, (“a binary, this-or-that, choice… when all of the protagonist’s attempts to go back to the way things were before… have failed”)

- CLIMAX (“when the protagonist decides and acts on the binary question”), and

- RESOLUTION (“the results of the protagonist’s decision”).

Revising: Easier to Do Than it is to Explain

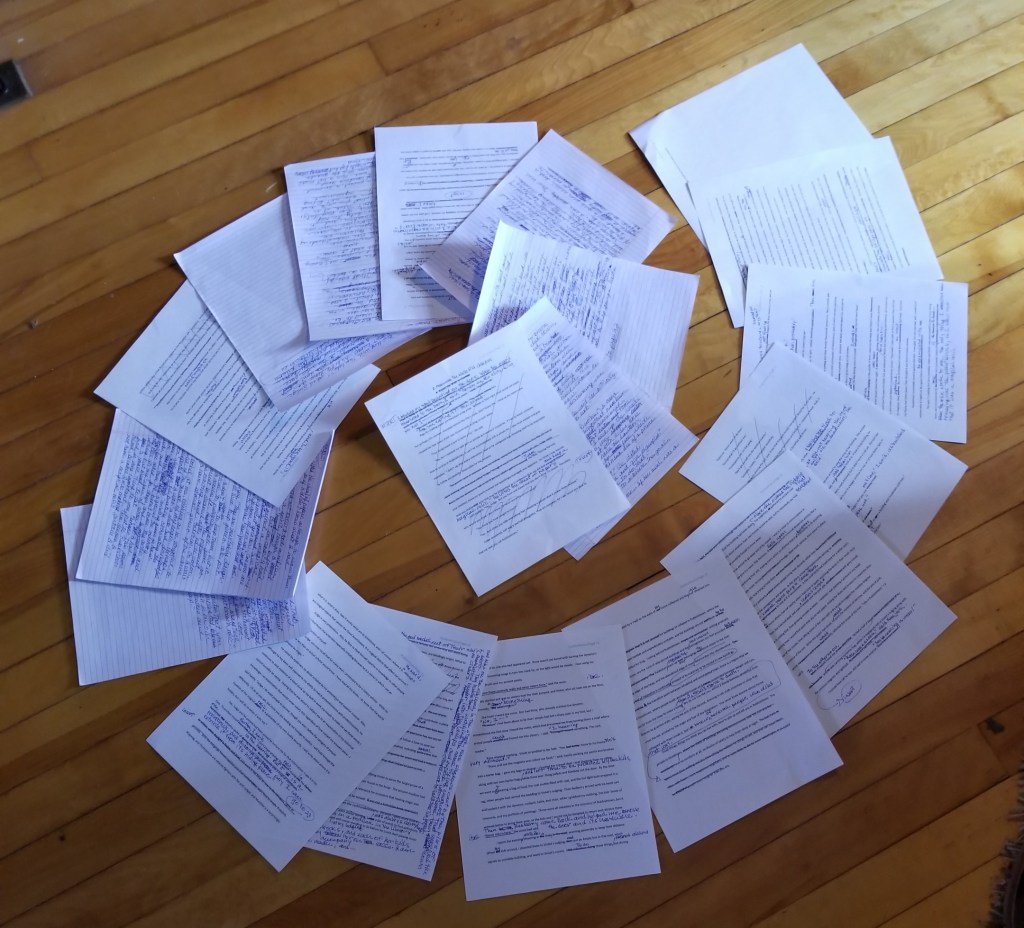

Once I had thought through the chapter’s story arc, I started relocating and revising the pieces of the chapter. I expanded the conversation between Painter and Judge from just a page to several pages, because I now knew why this conversation was important. In several places, I moved text forward or backward, to make the plot easier to follow. Since I’m a pantser, not a planner, I inevitably wind up with a lot of text that’s located where I happened to think of it, but not where the reader needs it to be. I deleted entire paragraphs or pages that had become unnecessary or had been replaced by better versions. I handwrote nine pages of new text, which fit into the surviving parts of the previous draft like additional ingredients for a teetering sandwich held together by narrative tension alone. (!!!)

Spending so much time revising this chapter allowed me to notice the themes that are strengthening its coherence. Walls and windows are important in this chapter, as are light and darkness. I don’t think I need to emphasize these themes, which seem to work as they are, but it is reassuring to discover them, evidence that my writer’s brains—all of them—are doing their jobs, often with no help from my conscious mind.

Leave a comment