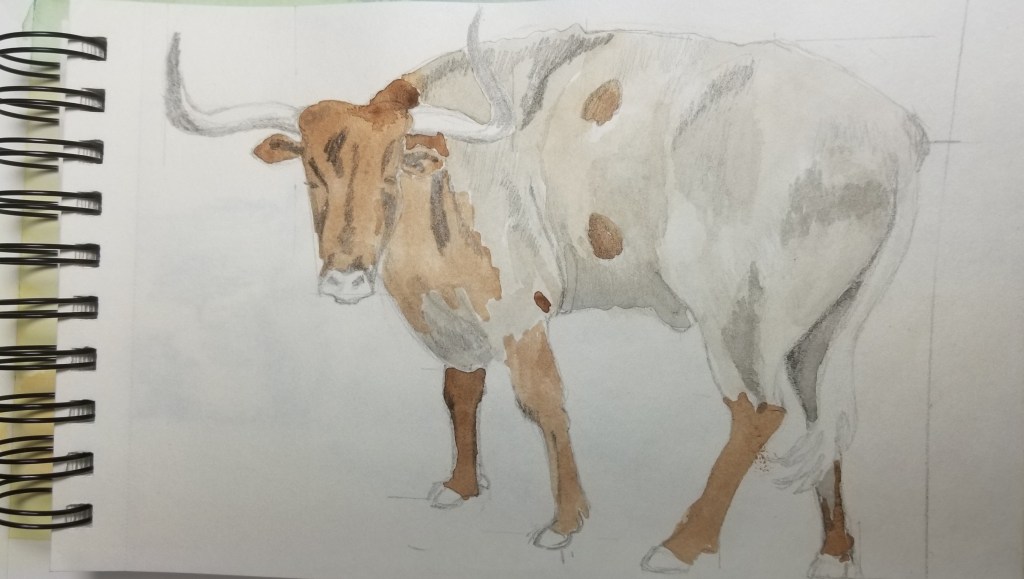

Also, information dumps, Spot the rescue cow, and continually learning to write.

I’ve revised the first chapter, after a fashion, and of course I now need to do it again, completely differently. As I mentioned last week, when I started drafting this book, I thought I was just doing some preliminary sketches, and was surprised to find myself writing the book. Therefore, this first chapter has only two short scenes, with very little dialogue, but it includes about 2,000 words of Painter’s biography that also delivers a lot of information about the world. I’m reluctant to label these 2,000 words an information dump since they’re very useful—at least to me. According to Painter, she needs to explain why she carries her entire supply of paint and paintbrushes with her wherever she goes, which requires her to go into a rather lengthy history. She’s covering all this information in order to teach Mstefna, her one-person audience, that a person must carry everything with them in order to survive.

Okay, so the narrative situation in my book is complicated. Painter, the narrator, has little writing experience, and most members of her society are illiterate. By contrast, she has gained a lot of knowledge by reading, and being the only knowledgeable person in the room might easily get her into the habit of delivering information. Also, information dumping is consistent with the story logic, since her task is to teach Mstefna how to survive.

Information dumps and Charles Dickens

However, everyone knows that information dumps are bad things that must be avoided. Or maybe not. Victorian novelists, writing to be read by a more leisured, less distracted populace, did plenty of information dumps. For example, look at the beginning of Chapter 11 of David Copperfield, (this link goes to Project Gutenberg’s free version of the novel), which in 800 words describes and provides information about the warehouse where young David is employed.

Now, scan down a couple of pages, and you’ll stumble across 500 words devoted entirely to what young David ate, where he purchased it, and what it cost. Read it—you won’t regret it. Dickens is an author whose work I read and re-read, and this book is a particular favorite. While his contemporary audience may have needed all this information and description, since it was outside their direct experience, for an American of the 21st century it is essential, because it makes it possible for an alienated reader to follow the story while becoming enchanted by its peculiar details.

Reading a fantasy novel is not much different from reading Dickens. However, the expectations of modern readers have changed, and I don’t want my uncommitted reader to delete the book sample they downloaded because they lost patience when a lengthy information dump caused them to be dumped out of the story. I must bow to contemporary expectations while also meeting the needs of my story, and I must resolve similar problems in chapters 2 and 3 as well.

Plan of Action

I’ll try a combination of strategies:

- Pull out some chunks of information and drop them into other chapters, to be incorporated when I revise those chapters. Cogitation is required: the information has to appear before or when it is needed.

- Add a scene to chapter 1 on which the information can hang like fruit on a tree. I have no idea what this scene will be, but the Muse will provide.

- Deliver the information in a compressed form. Maybe. Shorter is not necessarily better, and I can’t be the only reader in the world who prefers long books.

- Integrate the information into Painter’s purpose (such as by her telling Mstefna why this information is important.)

- Use the info dump as an occasion for Painter to comment on her own text, thus deepening her character. (“I may be telling you too much because I don’t know how ignorant you are…”)

Writing Backwards

By the time I was drafting chapter 4, I had figured out that I was writing backwards: I first decided what the “lesson” (chapter title) was, and then tried to invent a narrative to fit. But I needed to first write the narrative and then decide what it illustrated. (To be more precise, I composed various versions of the chapter titles at the same time I was writing the chapters.) When I did it the first way, I wrote a lot of exposition. Doing it the second way freed me to write the way I write, and to treat the chapter title as a revision problem.

This discovery that I was writing backwards demonstrates yet again that a writer’s brain doesn’t work how we think it does, or should. And, of course that writers never stop learning to write.

Leave a comment