I imagine you as one of three sorts of people: You’re interested in how a working fantasy writer thinks because you yourself are one, or because you’re a devoted and intrigued reader of fantasy, or because you’re learning about how a (not the) writing process works. This blog post gets into the weeds of world-building, and it’s pretty darned weedy. I was working on plot development and suddenly realized I need to know something about economics. Learning about economics enriched my world building, generated some new possibilities, and also made me aware of some new plot issues that I now have to resolve. Problem–> solution–> problem.

As I explain in this post, I’m currently working to incorporate new plot elements. While considering a plot twist, I realized that I need a more developed picture of how the economy operates in this post-apocalyptic fictional world.

I’ve never before needed to develop an economy as part of world-building. My need to do it now is an artifact of my decision to write a story in which the protagonist is stuck in place—she cannot travel due to the toxicity of her world. (A toxic environment is hardly an original trope in post-apocalyptic fiction, but it does a lot of useful work, both by restricting what is possible in the story, and by providing symbolic meaning.) This inability to travel exaggerates the importance of the place she lives. Her entire world is her settlement (Rubbishtown), plus two connected settlements that can’t be visited (the City and the farmlands). In order to properly explain how these people are managing to survive, I need a map of how all these places interact economically.

And if your eyes are already glazing over, I don’t blame you.

Let’s Start With a Definition

“Economies work by distributing scarce resources among individuals and entities. A series of markets where goods and services are exchanged, facilitated by capital, combine to make an economy.”

The protagonist, Painter, is an entrepreneur and head of household. Other household members contribute paid labor to cover living expenses. other household members mine for materials, a very dangerous job. Painter contributes to the pleasure economy of her town by providing art, which also serves a spiritual purpose, supplemented by a variety of side-gigs. Also, she participates in an informal system of mutual aid to her friends and neighbors, and she participates in the barter economy of her town, by exchanging services and by trading non-cash valuables (such as salt) for other items that are comparably valuable or useful (such as sewing thread). Barter items can be bought and sold for cash, which is required to pay for food and shelter, though the value of barter items fluctuates. Food and raw materials are in such short supply that everyone lives on the edge of starvation.

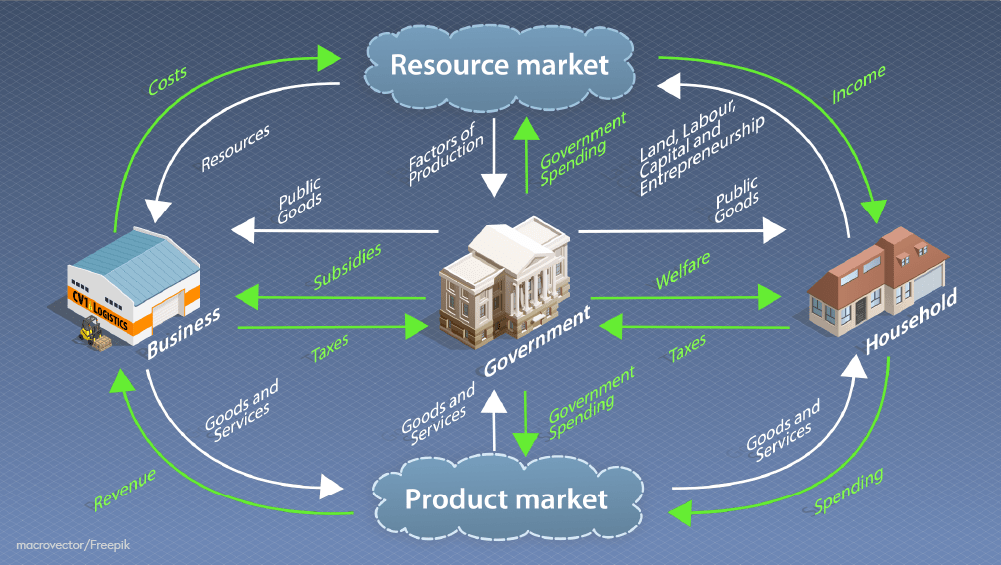

My Google search “How do economies work?” brought me to a website called Future Learn, which offered this map:

In this image, money (green) circulates clockwise while goods/services/resources (white) circulate counter-clockwise. For example, in my real-world household, my entrepreneurship (writing) goes counter-clockwise to the resource market and on to a business (Small Beer Press, my publisher), which turns it into a product (a book) which circulates counter-clockwise to the product market, to be purchased by another household, possibly yours. The money you spend on my book then travels clockwise from your household to the product market (such as Amazon) to the publisher, and every quarter my share of the income continues the clockwise journey to my household. So far, I hope, this makes sense.

The Economic Map of My Imagined World

Beginning in the Rubbisher household (upper right), moving counter-clockwise, labor and slavery enter the Resource Market, where people create (by finding) artifacts, machinery, and raw materials. (I decided to treat slavery as an involuntary service provided by Rubbishtown households.) The resources found by the slaves go into the City businesses, to be exported to a remote market on the other side of the sea, in exchange for imports of luxury goods such as silk fabric. These goods are only made available to people of the City. The resources dug up by secondary scavengers are purchased by the Rubbishtown businesses, which use them to create and sell local products–such as turning rags into paper–and to provide jobs for artisans. Those products are purchased by both Rubbishtown and Farmland households, and a percentage of the sale goes to the City as taxes.

Moving clockwise, beginning in the Rubbisher household, income from labor and entrepreneurship is spent in the Product Market on food, clothing, and lodging. The revenue from those sales goes into the Rubbisher businesses, which then use it to pay their workers and buy more raw materials.

The Plot Problem that Inspired this Mess

A piece of the economy collapses, and I needed to understand how that piece would affect the other components. The non-slavery labor (scavengers) which is contributed to the Resource Market by Rubbishtown households becomes unavailable due to an arbitrary regulation change. That causes a shortage in the resources available to the businesses of Rubbishtown, which in turn causes a shortage in the availability of goods to all three settlements. However, it wouldn’t have an impact on the import/export businesses of the City, which relies primarily on slave labor, not scavenger labor. I do want this labor problem to affect the City, but logically, the biggest impact would be on Rubbishtown. I may be able to make this effect on the City more intense, but I need to do some additional thinking about exactly what these scavengers do, and how the things they uncover enter into the economy. (I admit, I’ve been lazily letting this piece be vague because it’s just not that interesting.)

Sheesh, not more thinking! I want to get back to writing! However, the thinking I have yet to do might reveal some new potential for story development related to the interconnectedness and mutual dependence of participants in this small, extremely stressed world. That thinking won’t be wasted—it’s just not as fun as writing.

More helpfully, this exercise in economy-mapping has helped me understand better how the City is exploiting Rubbishtown, besides forcing the Rubbishers into slavery. In addition, I realized that the people of Rubbishtown are paying a tax on goods purchased with cash, but this tax doesn’t benefit them directly. The City protects the farmlands–but not Rubbishtown–from brigands. The Rubbishtown households have to pay a high price on food (expensive because it is taxed) but they’re taxed without representation. The City does whatever is beneficial to its residents, and sometimes the people of Rubbishtown go hungry. Finally, the people of Rubbishtown, forced to live in a more dangerous location, have a higher exposure to toxins than City people, and they live shorter and less healthy lives.

I already knew that Rubbishers were getting a rotten deal, but having thought through the economics of my invented world, I’m in a better position to write about it with greater complexity. It’s been a worthwhile, if grueling, exercise.

Leave a comment